The Crying Boy

About 15 years ago, at the start of my career as an educator, I observed in a Montessori school for the first time — and what I saw made me sick.

As I sat on this little wooden chair in the corner of a classroom — which had in it a couple dozen 3- to 6-year-old children and two adults — one child stood out to me: a horribly sad boy, no more than 4 years old.

The poor child was hunched under a table crying, and he basically stayed like that for the whole time I was in the classroom (for about 45 minutes).

When I first saw the crying boy, my impulse was to go over and comfort him. But I remembered that I had been asked to not interact with the children, unless they approached me, and so I just sat there, staring, imagining how tough it must have been for him.

What troubled me at that moment was not only the boy’s crying, but also that no one in the room seemed to care. All of the children and both of the adults (a head teacher and an assistant teacher) did nothing to help or comfort him. It was as if what I was seeing and hearing — a miserable child crying — didn’t exist for them.

That’s when I began to wonder about the other children in the classroom, thinking to myself: What are they actually doing in here?

My attention moved away from the crying boy under the table, to the rest of the children. As I looked around, I saw girls and boys happily engaged in all sorts of different activities and work.

Some were performing math calculations (into the thousands) using blocks and colorful beads; a few boys across the room were washing the tops of small tables; a girl was reading a book on a child-sized sofa chair; an older boy was helping a much younger girl to set up colored paints at an easel; another boy was writing out full sentences on a lined sheet of paper; a couple of children were sitting together at a ‘Snack Table’, chatting as they ate crackers and bite-size servings of cheese; a tiny girl, maybe a few months over 3 years old, was lying on the floor intently completing a wooden puzzle map of Europe.

Wherever I looked, children seemed completely focused on the unique task at hand, and with no prodding from an adult. I had never seen anything like it.

As I scanned the room, filled with this diverse group of preschool- and kindergarten-aged boys and girls, it dawned on me that there was no running, no yelling, no fighting, no ‘fooling around’. In fact, there was none of the usual difficulties teachers and parents can face with large groups of children — or even with just one or two!

It was remarkable.

But then my mind returned to the poor little boy, whom I had (shamefully I felt) almost forgotten.

The sound of his crying entered my awareness at once, as I looked over to find him still peering out from under the table.

Pity swept over me.

I imagined the boy saying to himself, in his own 4-year-old way, “All of these boys and girls are here enjoying themselves so much, while I’m stuck under this table crying like a baby!”

His miserable crying was such a dramatic contrast to the otherwise peaceful, humming activity in the room, that the situation seemed surreal. I kept wondering: Why is no one helping him?

The more I thought about it — and the more no one, neither the adult teachers nor any of the children, was doing anything to comfort the poor boy — the more I was getting sick to my stomach, and a little angry.

I wondered what kind of schooling this ‘Montessori’ really is, and what kind of witch of a teacher does nothing when a little boy is crying his eyes out?

(During my time in the classroom, the teachers never once comforted the boy. The head teacher barely spoke to any of the children, actually. For the most part, she just quietly went around the room, so quietly that at times I forgot she was even present.)

My visit was only for 45 minutes, and now it was time to leave. On my way out, passing the crying boy, I felt that there was something wrong with Montessori education — and I intended to tell the head teacher as much at a meeting I had scheduled with her for a couple days later.

The Montessori Witch

The day had come for my face-to-face meeting with the Montessori teacher, whom I now imagined wearing a black pointy hat flying to school on a broom — and I was looking forward to sharing my blunt feedback with her.

But when I arrived at the school, she greeted me with such grace and courtesy that I felt a little embarrassed to be imagining her as a witch whom I was about to interrogate. So as we sat down together in the teachers’ lounge, instead of jumping right into my criticism of her seeming lack of empathy in the classroom, I found myself just asking a simple question: “Why didn’t you help that crying boy?”

Her answer stunned me, because it seemed so ridiculous: “Mr. McCarthy, what makes you think he needed my help?”

You might imagine the look of disbelief on my face in that moment. But this woman had said it with such sincerity that I found myself mirroring her calm demeanor and just stating simply, “Well, he was crying.” Though I added for a slight jab, “I’m sure you heard it, no?”

With serene confidence, she responded:

Oh yes, I heard it, and I’m sure the children in the room did as well. But let me tell you what I also heard and saw, earlier in the morning, before you joined our class.

You see, when this boy — who is a lovely new child in our school and whose name is Lucas, incidentally — came into the classroom that morning, I had attempted to comfort him, for he was crying since his mom dropped him off. During the early morning, I had held his hand and walked with him around the room, pointing out select items on the shelves and introducing him to a few children he hadn’t yet met. Other boys and girls would occasionally approach us, attempting to comfort Lucas in their own way. One boy even gave him a hug and said, “It’s OK, your mommy will be back later. I cry sometimes too.”

Yet none of us could calm Lucas.

So I asked him if he’d like to be alone for a bit. He didn’t respond. I then gently let go of his little hand, allowing him to decide what he’d like to do, where he’d like to go within his new environment. He chose the very spot in which you saw him, under a table. And when he got there, he continued as he had since the morning began. That is, he cried.

Not long after that, you entered for your observation.

So there you have it, the context before you walked into our classroom. Now please follow me, so you can see how this story ends.

She then offered me her hand, quite literally, and guided me to the classroom that I was in only a few days earlier. (Being led by this peaceful, almost grandmotherly woman, I now felt like a child myself.) She took me right up to the classroom door, which had a small window, and she said softly, “Go on, take a look inside.”

As I peeked in, it was much like I had observed before: focused children enjoying all sorts of different activities. But then I saw what I knew she wanted me to see.

The crying boy.

The thing is though, “the crying boy” was no longer crying. In fact, if I had first come on this day he would have seemed like any other child in the room: engaged in a task, and happy.

The teacher by my side saw my surprise and said something I will never forget: “When you looked at that boy earlier in the week, you saw a pitiful child hiding under a table crying out for help. I saw a growing boy hard at work.”

“Work?” I asked.

“Yes. Work. Lucas was hard at work developing the seeds of independence and self-confidence that he will use throughout his life." And she continued: "You see, help comes in many ways. The children and I showed empathy for Lucas during his first days in the classroom. We helped welcome him to his new school home with warm greetings and simple words of encouragement. That was sincere, meaningful aid. But Lucas also needed some time alone, on his own. Not every child will need this, as some children acclimate to the classroom straightaway, but Lucas did. And that’s OK. Our help for him was in what we did not do. Instead of receiving our pity, Lucas experienced something children these days get all too infrequently: space to struggle a bit, to be a little uncomfortable — and then to feel the earned pride of picking one’s self up. Or, as the children sometimes put it, of doing things ‘all by myself’.”

------------------

Montessori Education

The simple yet profound outlook this wise teacher shared with me years ago, and the remarkable success of the boys and girls I observed in her class that day, are actually not unique. Their roots trace back over a century, to Rome, where in 1907, in a small classroom of 3- and 4-year-olds, a discovery was made about children.

This discovery — deemed “the secret of childhood” and praised by intellectual giants such as Alexander Graham Bell, Thomas Edison, and Helen Keller — would develop into Montessori, a distinctive approach to education now used across the globe.

"Montessori has helped me become the person I am." Stephen Curry, NBA superstar

Today if you visit an effective Montessori school (all Montessori schools are not created equal), you can see 2-year-olds using the bathroom on their own, 3-year-olds cleaning up after themselves, 4-year-olds reading and writing, kindergarteners doing multiplication, first graders drawing (from memory) all the continents and countries of the world. And if you Google “Montessori”, you’ll quickly find some of its successful grown-up alumni: famous artists, athletes, entrepreneurs — even the founders of Google itself.

Not surprisingly, Montessori education is increasingly in demand, with affiliated schools having long waitlists of thoughtful parents — from scholars and scientists to everyday moms and dads — all choosing Montessori for their children.

But what is Montessori, and how will it transform your child's future?

In the forthcoming book Montessori Education, you will discover Montessori for yourself and see how almost any child can grow to become an independent, successful individual. All it takes is the right environment, which begins with you.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

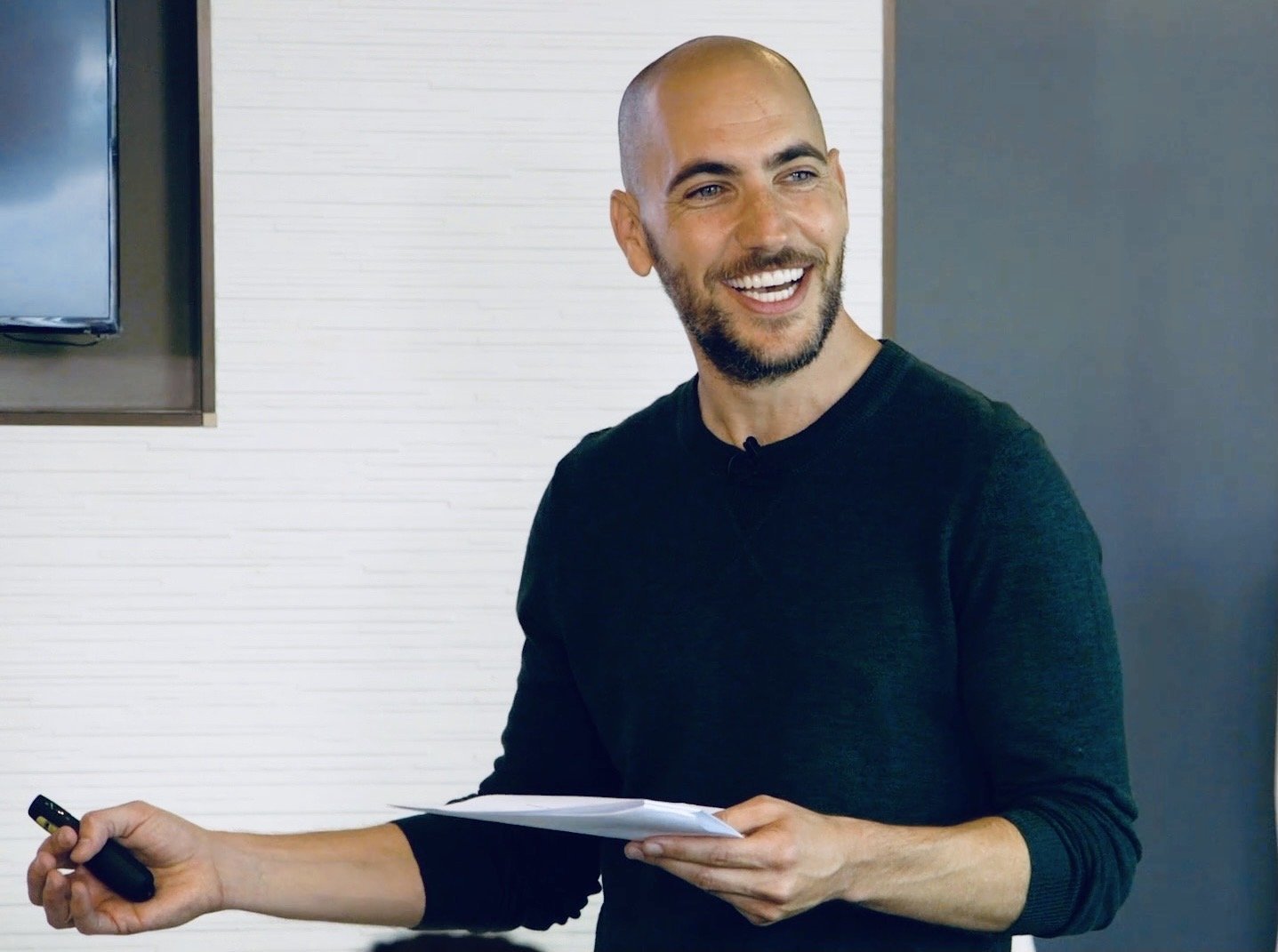

For over 20 years, Jesse McCarthy has worked with thousands of children, parents, teachers and administrators — as a principal for infants to 8th graders, an executive with a nationwide group of private schools, an elementary & junior-high teacher, and a parent-and-teacher mentor.

Jesse received his B.A. in psychology from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) and his Montessori teacher's diploma for ages 2.5 to 6+ from Association Montessori Internationale (AMI), the organization founded by Dr. Maria Montessori.

Jesse has spoken on early education and child development at schools around the globe, from Midwest America to the Middle East, as well as at popular organizations in and outside of the Montessori community: from AMI/Canada to old-school Twitter. Jesse now lives in South Florida where he heads MontessoriEducation.com and, alongside his wife, runs La Casa, The Schoolhouse.